Learn

History of Ikkanbari

HOME > History of Ikkanbari

1620s

-

1st Generation: The Arrival of Hirai Ikkan in the 1620s

In the 1620s, during the Kanei Era in the early Edo period, our founder Hirai Ikkan traveled to Japan from the Ming Dynasty in China.

It is said that Hirai Ikkan was a scholar who left China, accompanied by other young scholars, to escape from war at home.

He was also a certified lacquerware craftsman, a craft with a long history in China. Ikkan launched the craft of Ikkanbari using Japan’s high quality Washi paper and his own proprietary tecniques.

The Kanei Culture

-

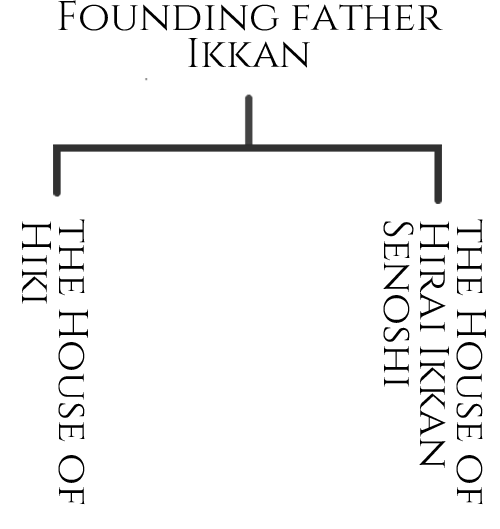

2nd Generation: Household split

The household split when the second generation took over from Ikkan, our founder.

One of these, the House of Hiki, produced implements for the tea ceremony and enjoyed the patronage of a practitioner of that art.

The other, taking the name Hirai Ikkan House of Senoshi, produced implements for use in daily life and enjoyed the patronage of the House of Hatanaka, a family of a local government official.

The name Senoshi was actually chosen by Emperor Reigen, Japan’s 112th emperor who reigned from 1663 to 1687. It is said that Emperor Reigen awarded the name when the family split after being introduced by the House of Hatakenaka. They were also awarded a Kikusui-mon family crest (featuring a pattern of flowers floating on a river), and their Ikkanbari wares spread throughout Japan under the employment of the Edo Shogunate.

-

Incidentally, when the family was split, Ikkan ordered that the two should not interact.

He believed that because their products and patrons differed, any interaction would lead to conflict.

In actual fact, interactions beteween both houses have been ceased to this day, and Ikkan’s true hope was that both houses preserve his spirit and techniques so that they would both mutually develop. This period was the time of the Kanei Culture, and Kyoto was the cultural center of Japan. Many privileged individuals supported culture and the arts as patrons at this time.

●

-

Later generations: Supporting daily life in the Edo Period

Countless Ikkanbari works were created as implements for daily life.

Some of the most common were O-Zen tray tables, O-Wan bowls, Buddhist statues, flower vases, writing implements, umbrellas and parasols, boxes for confections, and Kagura masks.For example, Ikkanbari tableware was very practical for the Shugun, because their light weight due to using Washi paper and lacquer made them perfect for use while traveling.

They were also good at keeping food warm.

At the time, tasters would check the Shugun’s meals for poison before he ate, and in the process of doing so, the food would grow cold when using ceramic or wooden tableware.

However, using an Ikkanbari bowl would ensure that the food would remain tasty without cooling off before it reached the Shogun.

●

-

4th generation: Yoshimune Tokugawa’s Telescope

Yoshimune Tokugawa, the 8th Shogun during the Edo period (in office 1716 - 1745) is widely known as the Shogun who started astronomical observations in Japan.

Yoshimune Shogun’s telescope that he ordered from the House of Senoshi still exists today. See more details from below

See more details from below

-

Published paper

Published paper

The eighth shogun Yoshimune Tokugawa's ikanbari large telescope

-

Offprints

Offprints

Available for reading at the Kyoto Institute,

Library and Archives and our atelier.

-

-

The length of the telescope is about 350 cm when its tube is extended.

Yoshimune’s telescope represents the pinnacle of technique and skill for its time.

●

-

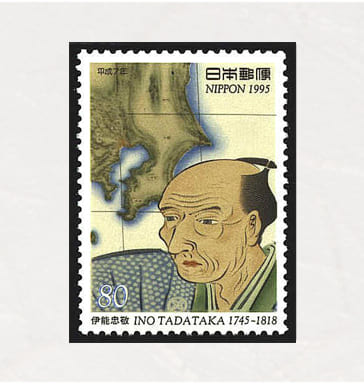

Supporting astronomical observation from the Edo period

Our forebearers continued to produce telescopes from Washi paper (for the cylinder) until the early Meiji period.

Another famous person who used an Ikkanbari telescope was Tadataka Inō (1745-1818), a cartographer who produced a map of Japan during the age of Tokugawa.

The House of Senoshi also produced telescope cylinders for Zenbei Iwahashi (1756-1811), a telescope craftsman of the Edo period.

●

-

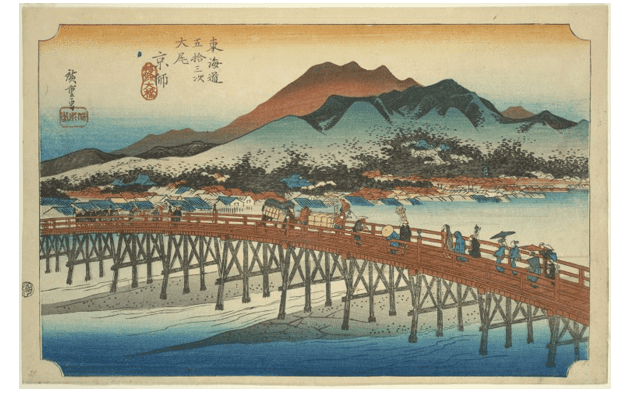

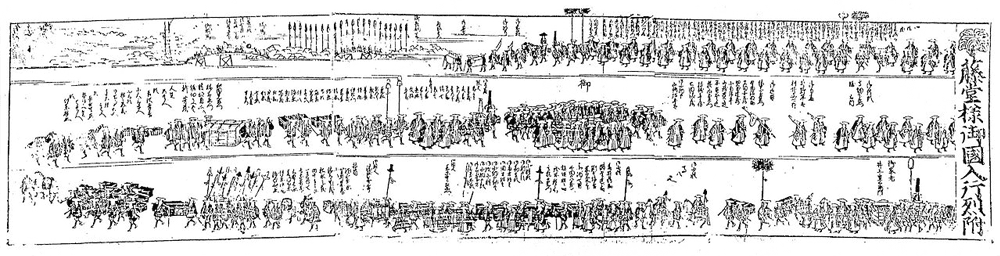

The popular Ikkanbari Kasa hats of the Edo Period

While this is not widely known today, there was a time during which the Kasa hats worn by members of the retinues of feudal lords on their regular processions to and from Edo were most commonly Ikkanbari designs.

-

Kasa hats worn in battle were of course made of metal, but a more lightweight design became a requirement for these so-called Sankin-Kotai processions which required every regional lord to maintain a home in Edo and spend every other year there.

Meanwhile, breaking and cracking was considered bad luck at the time, particularly on such a long journey, so wood was also considered a poor material choice if the hat should fall and be damaged. Accordingly, the House of Tokugawa ordered the House of Senoshi to produce Ikkanbari Kasa hats.

These hats, made from Washi paper and lacquer, were light weight, protected the wearer from wind and rain, and would not break when dropped. For that reason, the Ikkanbari Kasa hat became the norm.

Meiji and Taisho Periods

-

A Time of Challenge

With the decline of the House of Tokugawa, many Ikkanbari works were let go off, and ultimately found their way throughout the country and the world.

-

In modern times, this once supposedly lost Ikkanbari works have been discovered in store rooms throughout Japan. Unfortunately, modern people mistook the items for plastic and many of them were disposed of.

Showa Period

-

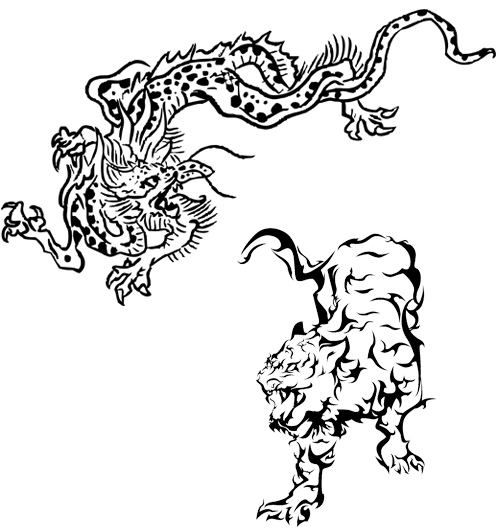

Ikkanbari dragon statue

With the advent of the age of mass production and the availability of plastic goods, the demand for Ikkanbari implements for daily life declined, and the items began to be produced instead as a traditional craft.

For example, a dragon statue was produced on order from a local official in Matsuyama City, Ehime Prefecture to be installed at the front of the city hall.1972

A tiger statue for Kakuei Tanaka

This order was received from Kakuei Tanaka in the year he took office as Prime Minister.

He asked for a tiger because the following year was the Year of the Tiger on the Chinese calendar.

The life sized tiger statue was produced using Washi paper for it’s light weight and portability, and because the breakage and scratching that can occur with wood or metal would be a bad omen.

●

-

14th Generation: Ikkanbari Today

The House of Senoshi has been persevered over the many generations, and the techniques continue to be passed down to this day.

As the 14th generation craftsman, I, Zuiho, learned the skills from my father, the 13th generation craftsman, and took over as head of the family in 2006.

Today I maintain an atelier in Kyoto.

Since around 2010, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has recommended our atelier as a facility to learn about and experience the Ikkanbari craft.

[Note] Above is based on the stories passed down in the House of Senoshi

-

Traditional Ikkanbari from the House of Hirai Ikkan Senoshi Atelier Yume Hitori

Address: Ukyo-ku, Kyoto Detail

Closed: irregularly (please contact us for operating days) Zuiho Onoe, 14th generation proprietor